Anu Ramdas

Lakshmi was always comfortable sharing her thoughts about her husband, Shanmugam. He was the shy one and never said much about personal things. Listening to Billie Holiday’s songs often brings back memories of the way Lakshmi used to talk about her married life to me. On some days it would be:

My man don’t love me

Treats me oh so mean

My man he don’t love me

He treats me awful mean

He’s the, lowest man

That I’ve ever seen

On others, she would admit,

He beats me, too

What can I do

On some other day, it would be,

But when he starts in to love me

He’s so fine and mellow

More often than not it was just the acknowledgment,

My man

Lakshmi and Shanmugam were Tamil migrants in Bangalore, working as construction laborers. When I got to know them, they had moved up the career ladder (yes, there is such a thing in construction work too), and had reached the coveted position of being the watchman of the building under construction. This promotion process is quite opaque; one is never sure why only one family of the dozens working at the site gets selected for it. Like any upward career move, it was envied, and discussed extensively by other aspirants. Significant parts of the discussions were carried on in whispers. Envied, because it came with the desperately needed perk of residential accommodation, the watchman’s family gets to live in the make shift shed within the building premises. Only a seasonal-migrant laborer knows how precious this offer is, and uncannily so does the contractor. It took me some time before I fully realized this move up almost always involved the sexual exploitation of the watchman’s wife and his female relatives by the contractors and their contacts.

That this violence was part of Lakshmi and Shanmugam’s lives used to become apparent whenever their periodic fights broke out. The little shed could never contain the raging fury of two humans; the domestic became public.

Lakshmi was of a slight build with very quick reflexes. Utensils, toys, stones, bricks or any handy object would be used to protect herself from the muscular Shanmugam’s verbal attacks. Her aim rarely missed its mark. He retaliated with bare hands. Both wore their physical scars in different ways. She’d cry when people enquired about her scars, receiving sympathy and advice; he remained coldly silent to similar queries, never letting anyone know his feelings about subjecting his wife to verbal and physical violence and being the recipient of counter violence.

This was violence between two individuals– man and woman, husband and wife. Or was it? How much of this domestic violence is linked to the violence that society bequeathes upon this couple? How much chance do they have of avoiding the many forms of violence including domestic violence, as migrant dalit laborers?

Given the state of domestic habitats available for the large majority of dalits, domestic violence is rarely domestic, it is usually very public.

Between Shanmugam and Lakshmi, domestic violence was about betrayal.

Whose betrayal?

Hers. She was supposed to mythically avoid sexual exploitation while still ensuring a roof over the family.

His. He was supposed to mythically protect his wife from sexual exploitation while still ensuring a home.

Society’s. It was expected to mythically not take advantage of chronically disempowered persons, whose labor, bodies and minds it could manipulate at ease.

I knew them as wonderful parents to 3 children with mutual dreams of a different world for them, tenderness between this married couple and the children bring back fond and nourishing memories.

~~~

Men from subaltern communities must confront the violence that tears apart some of their homes and families.

The above quote is a preface to a recent article in the national daily, The Hindu, where the author, V Geetha, has reviewed two books on violence and dalit women.

I wonder what exactly Shanmugam as a ‘man from subaltern communities’ should confront?

I hope this author can tease apart the distinctions of caste, gender, class, and separate the feminine from the masculine, demarcate the domestic from the public, in this brief sketch that traces my memories of one dalit family.

It should be easy to review and come up with some sound advice for this man. This wife beater. Why not just lock him up? Evil man. Beating up such a slightly built, overworked, mother of 3! Fill the damn jails with such low-caste and outcaste male brutes. Dalit women will become free of at least one form of violence – domestic violence. Well!

Since when did domestic violence become a characteristic of a specific caste, class, ethnic, geographic or subaltern group? If this is the take home message for ‘how to deal’ with domestic violence on ‘dalit women’, all one can say is that dalit society seems to exist in some kind of observational zone that has been marked off from the rest of the humans: that is, ‘their’ violence is being studied, the reason has been identified, and solution is being forwarded. Very scientific!

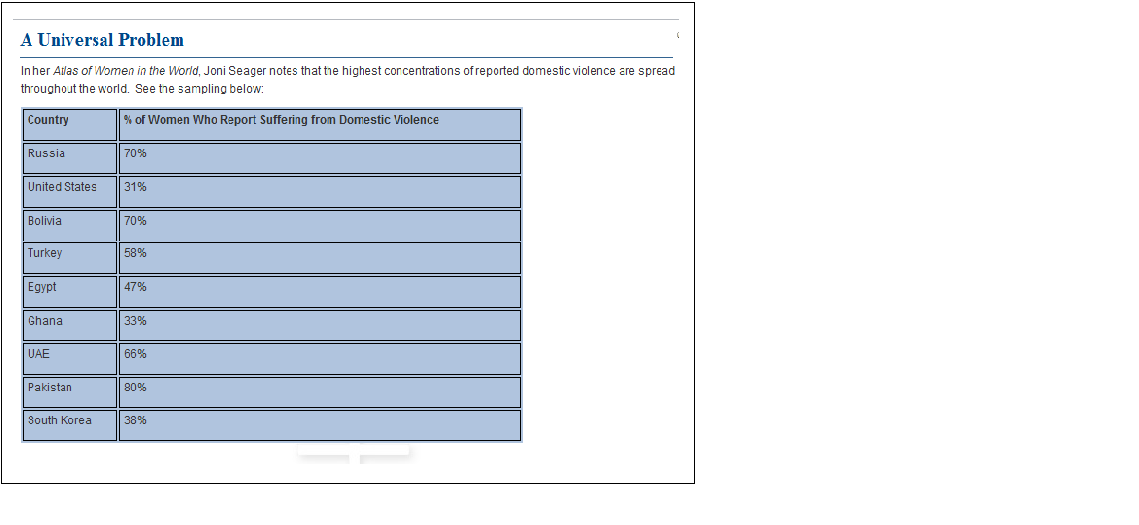

To repeat a well-known fact; domestic violence is a global phenomenon and it occurs across class, caste, ethnicity and geographies. No easy solutions are available against domestic violence in any part of the world for women, children and elders abused within the domestic sphere. However, possibilities of relief from domestic violence is variable across classes, castes, ethnicities and geographies, with the least possibilities for the ones at the margins.

I could elaborate further upon my other memories of domestic violence that I witnessed at close quarters; the Tamil language teacher in my Bangalore school who would turn up to class with a blue battered face – a brahmin woman, a literate, empowered woman with some options for relief in the caste society. And continue on with memories of domestic violence between a scientist couple in a top university in the USA– which became public only because a 911 call had to be made for the injuries sustained. Nobody would have guessed this highly educated, globally admired and much respected couple were throwing objects at each other with the intention to hurt. In the last case, the domestic is strictly domestic, and options for relief from violence for this couple in this society, are swift, definite and real, with little loss to personal status and privilege as well as employment and social opportunities.

Domestic violence is hell for dalit women, their families and the community at large. As it is for any other women belonging to any other group. A solution that rests solely on the reformative agenda of taming dalit ‘masculinity’ ignores the reality of inter-operating oppressive cultures in a caste society. And this leads to the question of stereotyping subaltern men, which only offers more hostile repercussions for the dalit woman and her family.

Migrant laborer communities are hired, retained and exploited efficiently because the oppressor systems have a superior understanding of the gender-dependencies of dis-empowered communities. Unlike some strands of easy feminism which intends to save the women and damn the men. Thereby double damning the women from marginalized communities.

Lakshmi is not the Tamil brahmin teacher, whose school went out of the way to accommodate her regular tardiness and absenteeism due to frequent injuries requiring healing time, ensuring her job security. There are no such inbuilt institutional supports for the Lakshmis, the working women of my community.

Though domestic violence on dalit women seems to receive microscopic attention from non-dalit scholars, authors and writers, the fact remains that the Indian society does not evolve any mechanism to provide relief options for dalit women other than the one locating her at the vortex of violence. The blame, reason and the conclusions of such studies is always placed elsewhere…. dalit masculinity (I have no clue as to what they mean by this) seems like a good enough ‘reason’ to be the analytic conclusion.

So what now? Lets go along with the advice and see where it might lead us: Dalit men, tame your masculinity. Step out of being complicit with patriarchy and voila dalit women become free of domestic violence. And with this, the dalit society would become a model for freeing itself from the problem of domestic violence. Then this model is reproduced in all the other castes, classes and ethnicities, all they have to do is just follow this route and women universally become free of domestic violence. Definite result: The data on cultures of domestic violence across the world dips and then vanishes. Darn! Why didn’t we think of this before?

In a caste society, for the dalits, domestic violence is often inseparable from societal violence. It is a manifestation of caste, class and gender exploitation, and failure of institutions from courts to classrooms. The ‘please take care of your dirty linen analysis’ is always pat and easy, especially when it can be thrown at the ones with limited or no options for relief from any kind of violence. More so if it leaves the structural edifice of caste untouched and leaves the complicity of the rest of the society, (including feminism that selectively ignores or focuses on caste), in the ‘violent politics of caste patriarchy’, happily unexamined.

We could leave this business as my nasty rebuttal to one reviewer who perhaps was restricting herself to the contents of the books and did not feel the need to connect domestic violence to anything beyond dalit men and women. Perhaps it is my caste location that reacts to her benign advice to subaltern men and read it as stereotyping the dalit men and extending it to its repercussions on dalit women.

But how many months is it since the whole nation was palpitating with righteous parental horror at Norway taking away the children of a NRI couple? The highest offices were pressed into action to rescue the nation’s credibility as a society that does not take lightly to hints that we may not be exemplary parents or have non-violent marriages and unsafe homes for children? Until the husband filed a report citing violence from his wife. And she later accusing him of the same. How soon do you think we are going to have scholars X, Y, Z studying domestic violence among, say, highly educated Bengali brahmins? And recieve from a book reviewer an advisory statement: ‘Men from bengali brahmin communities must confront the violence that tears apart some of their homes and families’?

It is a terrible waste of time to respond to the unexamined prejudice of one writer. But this review is placed at the end of a long process of stereotypification and initiates a new cycle of reproduction of stereotypes. The quote that is cited here captures this process, which is generated and maintained entirely on baseless societal prejudice that subaltern communities, particularly dalit families as having higher prevalence of domestic violence. This is gossip about dalits. Unadulterated prejudice receiving high academic patronage.

There exists no reliable comparative data across castes or classes on domestic violence in India. Which begs the question, from where does the design of these studies/books originate? If they are not based on data, they are only exploring notions and beliefs of the dominant castes: right from the design of the study to funding of the study, writing of such books, publishing and reviewing them in national newspapers- unchallenged at each and every level – a horrendously elaborate prejudice generating exercise.

Attempting to locate and substantiate selective negative traits at the individual-level, community level and caste-levels are experimental designs of Social Darwinism. The American war on drugs and the West led Islamophobia are such classic grand designs set up to prove the prejudice of the dominant cultures.

A statement like this: ‘Men from subaltern communities must confront the violence that tears apart some of their homes and families‘, which calmly puts non-subaltern men on a platform of non-violence and their families as stellar peaceful spaces is sociologically unforgivable. It excuses away the structural failures of institutions that are meant to perform protective roles for citizens from any kind of violence, including domestic violence. It puts no transforming pressures on education, media, faith systems and civil society.

Does pedagogy address domestic violence in school syllabi? I, like a lot of dalit students studied state syllabus, had never heard of NCERT textbooks as a student, so I am truly ignorant about how critical pedagogy addresses DV to school children. And media, incidentally almost all bollywood movies feature upper caste heroines who are shown being slapped around by the upper caste heroes. Where does that come from? Are the heroes borrowing from dalit ‘masculinity’? Or is it a reflection of chronic domestic violence in the families of brahmanized castes?

Such statements by writers are stunningly hideous viewed in any angle. Imagine a white woman writer delivering such a statement “Men from black communities must confront the violence that tears apart some of the homes and families” without comparative reference to domestic violence by white men on white women. In India you can say and write such things and still claim an anti-caste and feminist perspective.

Let me emphasize for the readers of this tiny space, dalit men writers have been the foremost citizens who have confronted domestic violence in their writings. Anyone with a passing familiarity with dalit literature will know that they have unsparingly revealed their participation in women’s oppression, there is hardly a dalit biography that did not address domestic violence experienced by dalit women with the most honest examination of women’s reality that any genre of literature has ever done. Dalit literature names, shames and forces changes in gender relations. The absence of such a narrative in literature from upper castes, does not imply absence of domestic violence in their castes; it only indicates an inability to confront that aspect by their conscience keepers- their writers, both men and women. But one can hope that this changes.

Anyway, please listen to the legendary voice of Billie Holiday and ponder a little over the lyrics. They hold the same magic for me of old Tamil songs playing out of Shanmugam’s small brown radio placed on the sand pile under the street lamp. The ones Lakshmi hummed to, her face glowing in the reflected flames of her stove. Shanmugam cradling the little baby to sleep.

Her man, her love.

Continued as Unpacking ‘Fulminations’: Caste and Patriarchy

This article is also published on Round Table India.

Image courtesy: Global status of women, 2009

—

PS: The internal discussions on domestic violence among Savari members has been of the view that battered women will be the ones who lead effective struggles against domestic violence. The essence of the discussions is best captured here:

Any fundamental change in the social order requires the changing of society’s collective consciousness. While changes in consciousness can and must occur at all levels of this hierarchically structured society, its source of nourishment will come from the oppressed. It will emerge from those least immersed in the thought patterns of domination. While no one in this culture can escape the devastating effects of the patriarchal imagination, those who benefit by it the least are best able to create a new vision.

Anu Ramdas: I am a computational biologist and I volunteer at Round Table India.

[…] read anu’s article, my man, here. […]

beautifully written, anu. this kind of flippant and casual reference to ‘subaltern men’ smacks of self-righteousness, which i believe has gone on for too long without anyone to even question…however, I also think one must engage deeply with the issues raised than respond in a defensive manner too quickly as well. keep writing.

written with lucidity and power.

thank you for this.

sharing with my students.