Jenny Rowena

My only preparation was to constantly tell myself that I love my body. And I was going to use it as a tool to get what I wanted in life and I was not going to be apologetic about it. So that was what Silk is for me. Therefore there is a certain innocence and yet she is who she is. She is this sexual animal, she is almost bestial in her sexuality.

My only preparation was to constantly tell myself that I love my body. And I was going to use it as a tool to get what I wanted in life and I was not going to be apologetic about it. So that was what Silk is for me. Therefore there is a certain innocence and yet she is who she is. She is this sexual animal, she is almost bestial in her sexuality.

Vidya Balan, in an interview given to CNBC program Beautiful People[1]

I identify with Silk to the extent that I also enjoy and celebrate my body. But it was amazing how she never used her head and never let anyone see the other side. It was always about the body and she was very unapologetic about it.

Vidya Balan quoted in Hindustan Times[2]

Vidya Balan’s highly objectionable remarks are surely part of an attempt to separate her upper caste, heroine self from the ‘deviant’ and subaltern vamphood of Silk Smitha.

In fact, as already discussed in the first part, Smitha’s vamphood was sketched out against the chaste upper caste heroines of her times like Radha, Radhika, Sreedevi, Sumalatha, Poornima, Urvashi, Suhasini, etc. Interestingly, The Dirty Picture does not give us a heroine figure corresponding to any of these actresses. However, the off-screen presence of Balan amply makes up for this. Film reviews and feminist readings that celebrate her boldness in taking on the ‘uninhibited’ sexuality of the South Indian vamp also help establish her off-screen persona as the controlled/virtuous woman in the whole Dirty Picture phenomenon. As against the cinematic role she plays as the vamp.

In this process, the caste-gender binary of the heroine and the vamp not only goes unexplored, but also gets reproduced. Continuing to interrogate this, in this part, I look more closely at Silk Smitha’s vamp persona in South Indian cinema, using it to think more about the vamp and the creation of the chaste, upper caste woman; and its consequence for ‘other’ women.

Silk Smitha’s vamphood

Silk Smitha thrived in the cinematic space reserved for the licentious, non-upper caste woman as vamp.[3]

Yet, there were some factors that differentiated her from most other vamps who came before her. First of all, unlike them, Smitha was given a chance to play roles that were more integral to the narrative. This made her pair up with South Indian Stars like Kamal Hasan, Rajanikanth and Chiranjeevi who were Mega Stars in the making at that time. This accelerated her impact and importance giving us many famous dance numbers:

However, in spite of her strong presence, spiced up with such steamy dance numbers, Smitha never played a significant role in the lives of these heroes. She was often rejected, discarded or forgotten as they moved on to smart but chaste and sexually inhibited heroines.

Another thing that differentiated Smitha from most other vamps was the fact she was very dark skinned. This was deliberately revealed on screen, unlike all those actresses whose fair skins were highlighted and dark skins hidden – both through an aggressive use of lighting and make-up. Her dark skin took on significance in the light of the fact that she appeared alongside heroes like Chiranjeevi and Rajanikanth who were fast moving towards a lower shudra caste/class location. Silk’s complexion helped in this context, as dark skin has been one of the most important markers of the lower castes in many cinemas of India.

Take for instance these songs. See how they locate both the hero and Smitha in the arrack shop and the granite quarry, differing greatly from the usual savarna/upper class setting of the bar-dance location, where Silk and the other vamps were brought in from the outside and were displayed as exhibits of a licentious non-upper caste femininity.

In both these videos the hero has clearly shifted to the subaltern location and Smitha is a woman they encounter there. However, here too, as in the other films, the hero’s commitment is never to Smitha. In fact, he has to separate from her to climb the caste-ladder to arrive at a pure, insulated, brahminic self.[4] Thus in a growing culture of shudra and lower shudra male assertion, Silk smitha’s dark skinned vamphood retaliated the ‘dirt’ and ‘bestiality’ of the lower caste woman whom everyone had to fracture and surmount, in the pursuit of social/caste mobility. She was used and thrown as part of this larger scheme, as a sexual object, a sex toy that was passed from hand to hand, touched and prodded and then discarded, just like the devadasis in the Okali and Siddi Attu rituals mentioned in the last part of this article.

So though Silk smitha’s image as a sex goddess grew to mythical proportions, being the embodiment of such a ‘dirty’, worthless, ‘use-and-throw’ woman, who marked the boundaries of caste/gender decency with her lustful body, this might not have actually translated into real power and privilege in her everyday life. It must have also contributed to her increasing marginalization within the film industry, driving her to a life of alcoholism and isolation, all of which came to an end with her suicide.

The Dirty Picture fails to engage with these issues that are crucial to understanding Silk Smitha’s star persona and life. Instead it slides into a ‘feminist’ account that presents her as a bold woman who ‘chooses’ to “use her body as a tool,” (as Balan puts it) to make her way up the film industry. Thus we see Reshma ‘choosing’ to seduce the reigning star, to take off her clothes, to display and make use of the wild sensuality she had brought in from her earlier ‘basthi’ life. The industry flourishes under her agential passion and many are in awe of her, as conveyed through the characters of the film critic, Naila and the film director, Abraham.

The aging superstar in the film is also trapped in her charms, preferring her wildness to the dutiful performances of his marital bedroom. His younger brother even wants to marry her! However, being less liberated and less radical and iconoclastic than her, all they can do is stick to conventional morality, thereby betraying and isolating her.

In other words, none of their choices are placed within the larger context of an industry where junior artists, extras and lesser members like the vamps (often from lower caste/class locations) are sexually exploited in a rather organized manner. Instead, a hypocritical attitude to sexuality is blamed even for such exploitation. Men are shown as caught in its mechanisms, which leaves them no choice but to hide their liaisons with her as a ‘dirty secret.’

How can we understand this sheer inability to represent the life and times of Silk Smitha?

Women and Difference

Dalit feminists and dalitbahujan political positions on the devadasi practice and other matters like sex work, bar dance, etc, emphatically identity them as oppressive traditions that exploit and subjugate lower caste women and communities. As J Indira writes about the devadasi tradition in her path breaking M.Phil thesis on Rape laws and Dalit women:

…Sexual oppression is an essential façade of social relations between dalits and upper castes. The oppression of the former relies as much on sexual assaults as on the other forms of oppression……..The devadasi system is one such way of perpetuating and institutionalizing such oppression. Devadasi, Dola, Adabapa, Kaneez etc are a few known religiously legitimised rapes.[5]

However, in Savarna feminist and other such theorization, the Devadasi tradition, lower caste dance forms, the bar dancer and the vamp are not similarly problematized. Instead they are often viewed as powerful and agential ‘male phallic symbols’ (as Jyotika Virdi defines vamps) and spaces that allow women to share a ‘functional equality with men’ (as Susie Tharu and K Lalitha describes the devadasi tradition of the pre-colonial times).[6] [7]

Problematic notions like ‘Brahminical patriarchy’ put forward by Brahmin feminists like Uma Chakraborty add strength to such positions.[8] Such thinking identifies caste as contributing to the oppression of Brahmin women by strictly controlling their sexuality. In contrast, dalit women are said to be “less oppressed within the dalit castes because there is less of the burden of the patrivrata ideology among them.”[9]

In short, savarna feminist theory even when referring to issues of caste differences, sexual control of women etc, still manages to locate the Brahmin and upper caste women as more sexually oppressed than other subaltern women, whose exploitation (in sex work, devadasi system, etc) is often viewed as sites of agency, subversion and resistance. It is such discourses that then trickle down to the making of films like The Dirty Picture, making radical feminists out of tragic, subaltern vamps, attributing all problems to the lack of sexual liberation in Indian society.

There is a serious need to centralize dalit feminist and other dalitbahujan articulations to move out of such problematic stands. In trying to do this the first problem one has to engage with, is the question of agency. Something that vamps, sex workers, bar dancers and devadasis are supposed to have in great abundance. [10]

Choice and Agency

While discussing feminine agency one seldom thinks about the framework in which we conduct discussions about it. For instance, do we thnk about agency only when we are talking about women like Smitha, located in the sphere of vamphood that mainstream feminist theorization would identify as agential? Look at how Kunda Pramilani brings up a similar question in her article “Dance Bars Ban Debate: Dalit Bahujan Women’s standpoint”[11]

O sisters we cannot forget the most recent Train Campaign we fought against the eve teasing. Please tell us what difference do you see between those road romeos and the male customer who pays to get sexually entertained?[12]

Here Pramilani is questioning the way in which some issues like eve teasing are taken to be oppressive by feminists as it concerns them, whereas bar dance, an area which employs dalit bahujan and adivasi women (and which dalitbahujan women condemn as exploitative) are not condemned similalry.[13]

Such contradictions arise because a caste/gender understanding, which is intrinsic to dalt adivasi bahujan positions are ignored by most discussions on sexuality. As shown in the next part of this article, this has constructed a hegemonic feminist politics for us, which is completely monopolized by upper caste women’s concerns with regard to sexuality.

However, before moving on to that discussion, I would like to extend and use Ambedkar’s theorization of caste as endogamy, towards a better assessment of the consequence of Smitha’s vamphood for subaltern women.

Endogamability

Some feminists argue that the sexual control that caste imposes on upper caste women is highly oppressive. However, it can also be argued that upper caste women are culturally endowed with an attribute or ability (be it real or just a façade) that presents them as being able to control their sexuality, which aids in the maintenance of endogamy.

In a caste society, such an attribute or ability, which can be termed ‘endogamability’ (extending the Ambedkarite concept of caste as maintained by endogamy) is highly useful and therefore given great value and respect. Thus it comes to frame the very nature of dominant femininity in our context. Women incapable of this are pushed outside the notion of womanhood, losing access to all kinds of concessions and benefits. In short, from being treated with respect, to gaining protection from caste/patriarchal violence, endogamability is a privilege, which provides a much more liveable life for women.

The vamp who is unable to keep her sexuality in check is nothing but a loud symbol of the absence of endogamability, cleverly mapped on to the lower caste female body. Her greatest consequence for subaltern women is that she works to push them outside the definitions of femininity thereby marginalizing her and legitimizing violence against her. The heroine, on the other hand, is the perfect embodiment of endogamability, with which the upper caste woman is legitimized to stand at the powerful centre of the caste Indian family, nation and modernity.

Adivasi, bahujan and Dalit women who have been historically constructed as lacking in endogamability (in varying degrees) keep encountering the bitter effects of this in their daily lives.[14] Silk Smitha too must have lived and died, marked and haunted by such a lack.

How can we then celebrate this ‘lack’ as agential and empowering ?

Instead, it would be more helpful to extend this reading of Silk Smitha’s vamphood to other areas of feminist thought and action, so as to strengthen the caste/gender analysis. I shall start to do this in the next and final part of this article.

References

[1] http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tq0pzEy5l6s

[2] http://www.hindustantimes.com/Brunch/Brunch-Stories/Beauty-and-brains/Article1-780555.aspx

[3] To expand some of the arguments in the first part – from 1957 films likeMother India to the 2012 Cocktail, all the virtuous women on Indian screens have almost always appeared under and in upper caste names and locations. In great contrast, vamps – who appeared as lowly bar dancers, molls, ‘gypsy’ dancers, performers of various cinematic versions of lavani, koothu and other such lower caste dance forms – have all been clearly and loudly situated in non-upper caste locations. The shouting out of names like Chin Chin Choo, Shabnam and Monica, during the performance of cabaret numbers often worked to provide these markers. If not these, then there were others. Thus we never got to see a Sunitha or Bharthi or Sita and down south, a Gayathri or Lakshmi as a vamp who is a bar dancer or a ‘gypsy’ character. Even today when the vamp is said to have merged with the heroine, we can see how ‘other’ locations and lower caste costumes, references and dance forms maintain the vamp in a subaltern location. In fact, now when the heroine herself is taking on more features of the vamp, the shouting out of lower caste names like Munni, Sheela, Chikni Chameli, Anarkali and Jileebi bhai have only turned more aggressive. In fact, in spite of all the noise about new films that are said to explore radical themes with the presence of bold heroines and themes, look closely and you will see the same patterns of caste hindu morality working. In spite of all the new multiplex experiments, Indian cinema has yet to budge from its given, caste enhancing role.

[4] What is interesting here is that in some such films Smitha was sometimes contrasted to chaste and virtuous, lower caste/class women, who put forward a caste hindu femininity of extreme chastity and control. Smitha’s first movieVandichakkram (third video) itself is a good example of this, where she was contrasted to Saritha’s character.

[5] J. Indira, “Study of Sexual Violence: A Case of Rape against Dalit Women.” M.Phil. dissertation, University of Hyderabad, 1997.

6 Jyotika Virdi – The Cinematic Imagination: Indian Popular Films as Social History, Susie Tharu, K Lalitha in the Introduction to Women Writing in India: 600 B.C. to the Present.

7 In fact, the Devadasi system is highlighted again and again as providing economic independence, property, higher ritual and social status to the devadasis in comparison to upper-caste domestic women. (Uma Chakraborthy, Janaki Nair, S Anandhi). This notion is so entrenched that even when “the recovery of unromanticised acounts of the devadasi system by dasis themselves” correct such accounts they are still blamed for denying “any subjectivity other than that of victim to the devadasis.” (!) Mary E John and Janaki Nair in the Introduction to A Question of Silence?

In fact the very notions of the good woman and the licentious woman (which is intrinsic to the Devadasi tradition) are said to be created when colonial forces judge and condemn this system. (Susie Tharu, K Lalitha in the Introduction to Women Writing in India: 600 B.C. to the Present).

Attempts at abolishing these exploitative caste practices that many dalitbahujan leaders like Ambedkar, Periyar, Sahodaran Ayyapan, etc., had strongly condemned, are viewed as a meek submission to colonial injunctions based on Victorian notions of respectability. (Susie Tharu and K Lalitha, Janaki Nair).

[8] Problematic as it fails to really talk about the power differences between women and see all women as similarly caught in varied forms of caste patriarchies (with Brahmin women as most severely effected with regard to sexuality). And even more problematic when used to deal with such problems by shifting the discussion to a new understanding of difference whereby powerful women are called on to take on the dalit woman’s unique voice (as proposed by Sharmila Rege in “Dalit women talk differently: A critique of Difference”).

[9] Chakraborty borrows from the writings of Kancha Ilaiah to come to this conclusion. However, Ilaiah himself is caught in a larger feminist construction of lower caste women as more liberated.

[10] As one of the comments (by Meena Seshu) which appeared as a response to the first part of this article hesitantly puts it:

This article….lacks by ignoring the intersection of Silk’s own understanding of her image. For her – Was it the best way to make money? Was it the best way to gain popularity? Surely she must have had some understanding of her life and its meanings – both for herself and society around her? To imagine her only as a passive recipient is very limiting, in my opinion.

[11] She says this while trying to summarize the decision taken by dalitbahujan women from Bombay to support the Maharashtra Government’s decision to ban dance bars and she is addressing feminist activists who are up against the ban.

[12] See http://www.scribd.com/doc/14066106/JulyAug-2005 for the Insightissue with this article.

[13] Talking about eve teasing, Caroline and Filippo Osella (in their book Men and Masculinities in South India) have argued that eve teasing in Kerala, for instance, is a complex activity allowing some communication between men and women in a sexually segregated society and cannot be easily framed as “an expression of hierarchic heterosexuality.” However, such ‘complex’ and ‘nuanced’ positions are never adopted by savarna feminists regarding issues like eve teasing, especially in feminist political articulations. However nuance and complexity is called for the minute ‘others’ start articulating ‘their’ political positions.

[14] One quick example of such an experience (articulated in public) that I can think of, are these words from Swathy Margaret’s powerful piece on Dalit Feminism:

the ghost that stared at me was not the thought of a hanging female body but it was my own body which is Dalit and woman and is as vulnerable as Suneetha’s. The stories of Dalit women being used and thrown by upper caste men, told and retold by my mother came back shouting loudly in my ears. ( 03 June, 2005 Insight.)

Read Part I of this article here and follow the discussion on it here.

Jenny Rowena teaches at Miranda House,Delhi

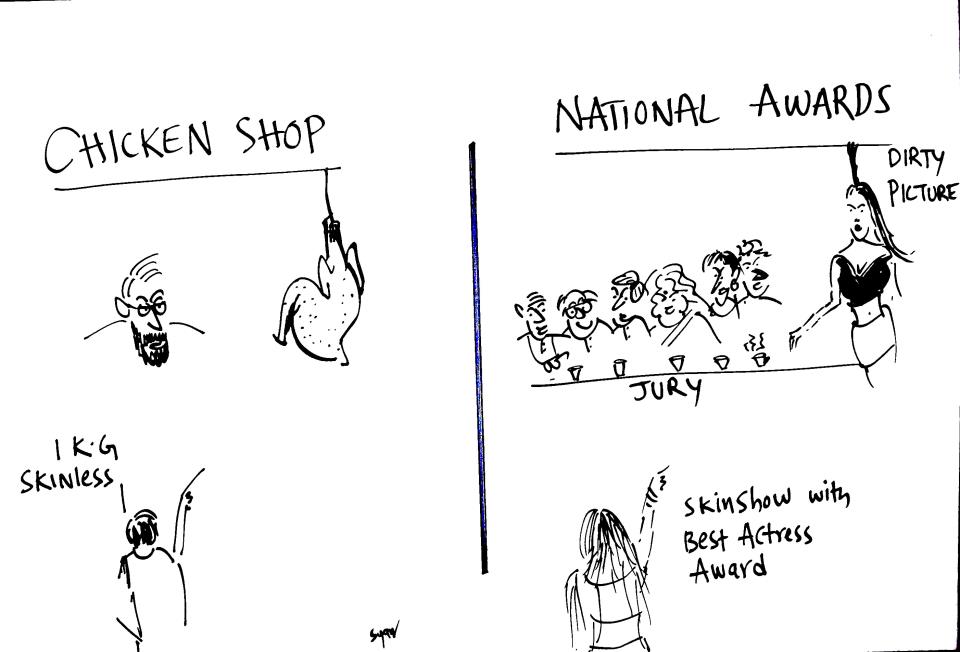

Cartoon by Unnamati Syama Sundar

~However, it can also be argued that upper caste women are culturally endowed with an attribute or ability (be it real or just a façade) that presents them as being able to control their sexuality, which aids in the maintenance of endogamy.~

I would like to understand this better. Could someone help?

hi Jenny,

This is Banko Kabida here. I am working with the kamble amd maang community who were all formerly coerced into the devdasi system. There is this organisation called MASS in Belgaum. Here 4000 odd women from the community have quit the dedication and are strictly monitoring the forced dedications. These women are using marriage as their claim and space to reclaim their life with dignity. They have a very good legal cell to protect all the legal entitlements of these women.