Joopaka Subadra

This is the second excerpt from her recent online talk organised by Bharata Nastika Samajam and Scientific Students Federation. Read the earlier one here.

The Savarna women say they clean their kids’ shit, in their homes. Then what about these women who clean the shit of all public, outside homes? Why don’t they talk about these women?

The Savarna women say they clean their kids’ shit, in their homes. Then what about these women who clean the shit of all public, outside homes? Why don’t they talk about these women?

If as you say all women are equal, you’ve to talk about all women, from the top to the bottom, to pataal, right? You’ve to climb down all the rungs of the caste system, talk about the problems of women at each rung—what are the problems of the Brahmin women at the Brahmin step, what are the problems of the Shudra women at the Shudra step, what are the problems of the Dalit women at the Dalit step, what are the problems of the Adivasi women at the Adivasi step? Why don’t they talk about all these women? Why are they erasing all these problems?

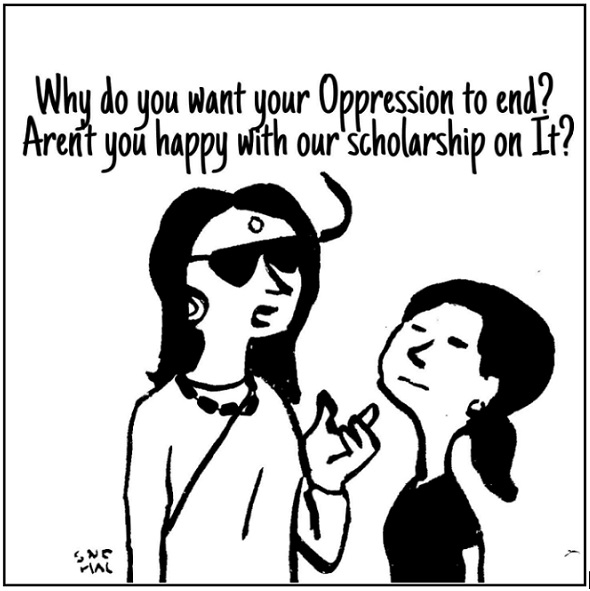

Their histories, their experiences, their languages, their voices—why don’t you allow them to come out? Even if they do come out, (you decide) what they should talk.. they should talk only to the extent of patriarchy. They should talk only within the frame you directed, organized, built. We should only talk about patriarchy, as determined by your framework.

But in our castes, patriarchy is limited to the home. They call power over structures, institutions as patriarchy, they call even power limited to the home as patriarchy. How unjust! No one pays attention to this. They talk of histories as men’s histories. Which men’s histories? Literature as men’s literature. Which men’s literature? They don’t talk about that.

They are Brahmin men’s literature, histories. Kshatriya men’s histories, dominant caste men’s histories. What about the men and women of our castes? No, there would be nothing about them there. The knowledge gained from your experiences, your ways of looking at histories, your methodologies, and your literary norms, your political ideologies—all of it is within your purview of understanding, thinking. You’ve not gone beyond that, to the bottom of society.

Our so-called patriarchies, if you take a village as a unit: our patriarchy provides chappals for everyone in the village. It washes the clothes for everyone—men, women, children—in the village. It shaves everyone’s hair in the village. It washes their sores and pus-filled wounds. All this is patriarchy? All the tools and implements of agriculture– our patriarchies produce all of them.

Tell us what your patriarchies do. Your patriarchies have taken control over society, societal institutions, men and women, including their own women, and institutionalized their power. Your patriarchy says if I die she has no right to live either. She should be burnt with me. Your patriarchy says, if I die, you’ve no right to remarry. You’ve no right to divorce either (when I am alive).

To fight that, you undertook many struggles, national struggle. And were freed from all that, from sati.

But there are no such strictures in our castes. If the man dies, the woman has a right to live. There are democratic freedoms here. You won’t talk about this. If I need a divorce, if I say, I don’t like this, we can separate and go on our own ways.

To give you those rights, Ambedkar waged a big battle, by bringing in the Hindu Code Bill. Wasn’t it you—Sarojini Naidu and other big figures—who opposed it? Ensured that the bill didn’t pass? Your thinking was, an SC man, an untouchable man, shouldn’t propose a bill in your favour. Because your men would lose face, their honour would be lowered.

You had no right to remarriage. In our castes, if the husband dies, the wife could remarry. If there is a divorce, you can remarry. Remarriages are very common amongst us.

Your patriarchies subjected you to such injustices, to such unjust customs. That is patriarchy. And what doesn’t cross the home, and has no power outside the home, what remains as domination, control within the home—should we call even that patriarchy? This question needs to be asked, very seriously.

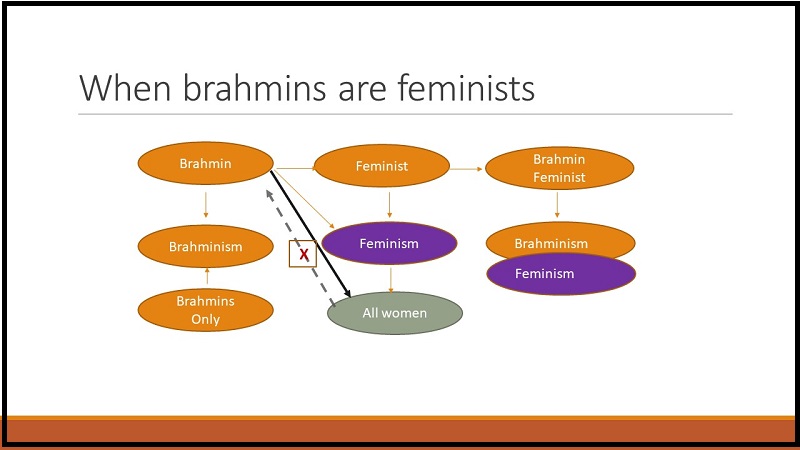

We’ve been talking. That these are not patriarchies. Feminism has brought in a new thing called Dalit feminism. Even that was decided by them. Sharmila Rege from Maharashtra.

There are MBC women, have they (Savarna feminists) brought in MBC feminism? There are Adivasi women, have they brought in Adivasi feminism? It is because we (Dalit women) are talking because our voices are strong, they brought in Dalit feminism (to slot us). We don’t like it. We don’t like to say ‘Dalit feminism’. We don’t like the term ‘feminism’.

Where did you bring the term ‘feminism’ from? From the western countries, from the dominant (white) groups there. You bring it here to impose your domination over which classes? We go the universities, to the centres of education to get our degrees. There, (they don’t wish to know) what are our origins, what are our histories, where have we come from, from what soil have we come, from what untouchability have we come, from what humiliations have we come.. We search to see if we can get any answers to those questions at these places. To see if we can find any solace here.

But we’ve to become feminists there at the university. Look at all the universities in India. You’ll find women’s studies centres. All of them are under the control of Savarna women, except for one or two. Look at all of them. I need to learn about patriarchy that is not mine. And patriarchy is a war against men.

We have caste wars before us, our immediate everyday concern. I’ve to leave that and wage war against our men, who are slaves themselves? Except at home, he has no power anywhere outside. How can you call even that patriarchy…?

~~~

Joopaka Subadra is a poet, writer, critic, and a significant figure in Telugu literature and anti-caste struggles.

This was translated from Telugu by Naren Bedide (Kuffir)

You can read her interview on Prauddha: Journal of Social Equality