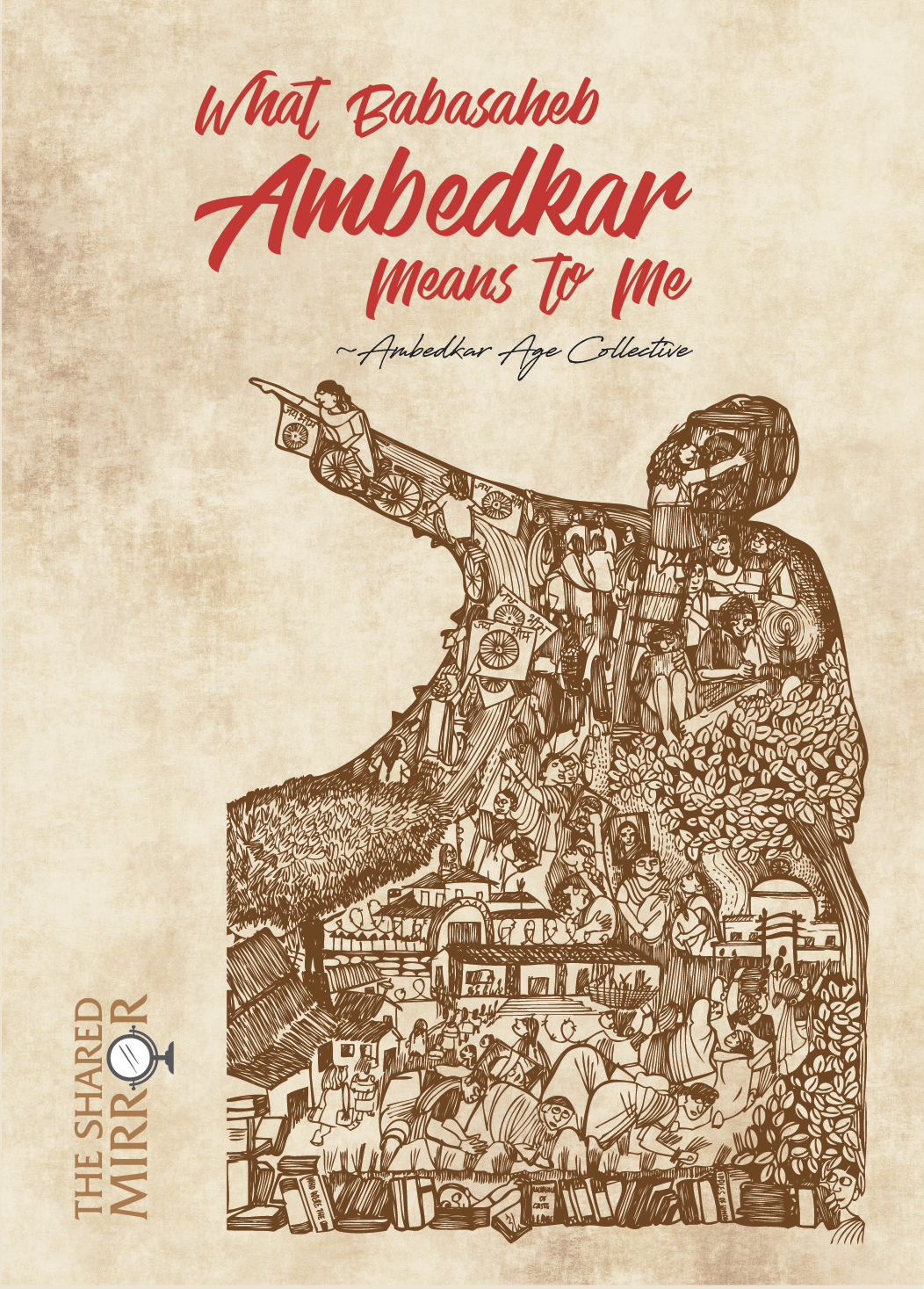

Editors, What Babasaheb Ambedkar Means to Me

We thank our readers for their warm reception of our book What Babasaheb Means to Me. Figures from one of our websites, The Shared Mirror show that we have crossed 3,500 downloads. The actual number of downloads are likely to be higher since the book is being downloaded and shared through other platforms such as Amazon, Whatsapp groups etc.

We thank our readers for their warm reception of our book What Babasaheb Means to Me. Figures from one of our websites, The Shared Mirror show that we have crossed 3,500 downloads. The actual number of downloads are likely to be higher since the book is being downloaded and shared through other platforms such as Amazon, Whatsapp groups etc.

Two popular demands from readers have been a) to bring out a print version to reach readers who do not access the web or are not comfortable reading full texts in digital formats and, b) to have it translated to other languages like Hindi and Marathi. We are glad to announce that friends are raising resources to bring out a print version shortly.

After the book was published, a reporter from the Hindu got in touch with us and sent us the questions below. Although the editors of the book responded to these, it was not published. Today, we are publishing this on Savari.

1. When did you conceptualise this and why?

As we point out in the preface of our book, what we conceptualized at first was not the book itself, but a series of articles on the websites Round Table India and Savari, to celebrate the 125th Ambedkar Jayanti. When we called for these articles, we were aware that we did not need a particular occasion to celebrate a leader who stood as tall as Dr B R Ambedkar, fondly called ‘Babasaheb’. What we wanted to do, as we mention in our ‘Call for articles’ is to remember the ideals and values he stood for, the humanity he espoused, and his anti-caste thoughts that lead our society to realize its full humanity.

Lest the rationale for these essays is lost, we have published the ‘Call for Articles’ that we put out on our websites in the book, before the essays. This is to ensure that the readers fully grasp the context of the book.

2. What is the relevance of a text like this right now, at this point in time?

We would think a text like this is relevant not just at this juncture, but at all times. While there was an immediate context to the ‘Call for Articles’, the essays that we received as responses convinced us that we needed to document this for posterity. The wide variety of ways in which Babasaheb is remembered – and we say it in our preface – is proof of the lasting relevance of his thoughts, of its contemporariness, even though he has not been around for the last 60 years. Often, critics say that his followers worship Babasaheb, as Arvind points out in his essay. This book should lay such reductive notions to rest. The writers come from various locations – across regions, castes, religions, classes, and gender – and you have to remember, they all had widely divergent paths that led to Babasaheb. If there is one single pursuit that unites the authors, it is their recognition that caste needs to be annihilated, for the sake of all our humanity. The several ways in which our writers engage with Babasaheb and his large body of work would immediately make it clear to a reader that it is a purposeful activity – simultaneously cerebral, spiritual, and emotional. Even though our essays say how each author relates to Babasaheb, we hope it will open for those who are yet to discover him, to the inquisitive mind that stumbles across this book, an instinctive desire to know more about this man, his ingenious mind, the deep compassion that drove his pursuits, the steadfast ethical positions that he embraced.

3. Do you see a changing trend in Ambedkarite politics? Does this book correspond to that trend?

As editors of the book, we don’t want to be indulging in the analysis of the changing ‘trends’ of Ambedkarite politics for these reasons: Annihilation of caste is an ongoing movement of the Dalit-Bahujan over centuries. It is, as mentioned earlier, stemming from a conscious and deep thought process, from the realization that humanity binds us all. If it doesn’t, it should. This is not a fashion to have a ‘trend.’ Nor is anti-caste work a choice to those who realize what it means – it is a striving towards equality, and there are no shortcuts to get there. Analysing ‘trends’ often presumes a uniformity over a period, or a region, or some such category. What does this book offer by way of that except the time in which it is compiled – now? Thoughts presented in this book are at times from the present age, but often are experiences, memories, thoughts, and struggles of previous generations. Every individual who is conscious of the evil of caste supremacy does something towards its annihilation: sometimes it takes the form of a mass movement, sometimes it is an individual act, sometimes it is a book, sometimes a literary movement… This is one such.

4. You’ve featured poetry and works of art in the book. Could you expand on the need/role of art in resistance, and revolutionary politics?

Art, poetry, songs, sculpture, symbols are all important means through which the Bahujan have advanced anti-caste work. Pradnya Jadhav and Gouri Patwardhan write in their articles about how in Maharashtra, songs and singers – Wamandada Kardak, Vitthal Umap, Balanna Nimal etc. – took Babasaheb to the people. If Swati Kamble writes that ‘We are all Ambedkar,’ Syama Sundar draws it. These are people who have probably never met or interacted with each other, and grew up in very different parts of India. The same assertion means different things in different contexts, and yet, here they are, having similar thoughts about the same person. For the editors of the book, all that mattered was that what was expressed responded to our call for articles. There was no question of privileging essays over art and poetry – in fact, quite the contrary, the latter seems to be the lifeblood of the book!

5. What is it that you hope the publishing of a book like this can achieve?

If you notice, several of our writers like Sruthi and Suravee point out how the educational system excluded Babasaheb, how they had to discover his thoughts in other ways, despite his summary exclusion in schools. It is our hope that this book will make some readers question the educational curriculum that blurs the contribution of one of the finest thinkers of the country! We also hope this book will in the least, spur introspection and reflection among readers about their respective roles in the annihilation of caste. Perhaps, it will lead some to Babasaheb’s original writings.

At the risk of repetition, let us add that we think it will dispel some myths about Ambedkarites, Ambedkarism, and anti-caste thought, for instance, that it is for ‘dalits’, ‘his followers Worship Ambedkar mindlessly,[ that caste is a thing of the past.

Let us remember, as Ravindra Goliya writes, that Babasaheb is for all of us.

—